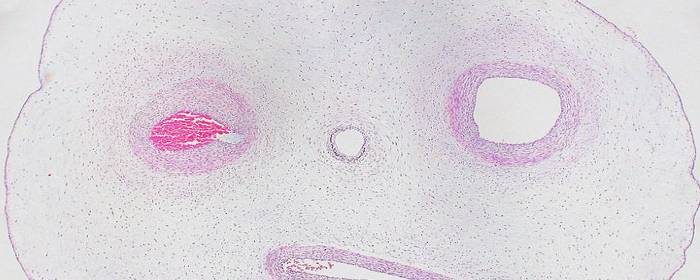

Wharton’s jelly is a rather unique body fluid. It is the connective tissue found within the umbilical cord. While Wharton’s jelly is connective tissue, it more closely resembles gelatin. Historically this material was discarded as medical waste; however, Wharton’s jelly has been shown to contain a number of therapeutic substances. Among these healing substances found within Wharton’s jelly is an abundant supply of mesenchymal stem cells.

One of the most intriguing features of Wharton’s jelly is that it contains a virtually limitless supply of mesenchymal stem cells. There are about 4 million new births in the United States each year, 5 million in the European Union, and over 100 million worldwide. The potential pool of cells is staggering when you consider only a small amount of Wharton’s jelly can contain millions of stem cells. Notably, Wharton’s jelly is usually discarded after the delivery of a healthy baby. If this material could be donated instead of discarded, researchers believe they have found an abundant, renewable resource from which to draw mesenchymal stem cells.

However, the abundance of Wharton’s jelly is not the most impressive feature of the substance. The stem cells found in Wharton’s jelly are rather unique. Perhaps most importantly, the cells are immuno-privileged. This means they are not readily recognized by the immune system. Consequently, the stem cells can be taken from the umbilical cord, purified, and then injected into a patient with little risk of the patient having an immune reaction to the cells. These particular mesenchymal stem cells are also interesting because they are relatively “primitive,” which means they have some of the same properties of embryonic stem cells. However, Wharton’s jelly can be obtained without controversy, while harvesting embryonic stem cells from aborted tissue remain highly controversial.

Stem cells taken from Wharton’s jelly are already being used in some clinical studies. For example, researchers in one clinical study injected type 2 diabetes patients with Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Within six months of treatment, 7 of 22 patients became insulin-free and 5 were able to reduce the amount of insulin they needed by more than 50%. Only one patient out of the 22 did not respond to the stem cells at all. The cells have also been tested in systemic lupus erythematosus, better known as simply lupus. Forty patients received Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells intravenously. Thirteen patients enjoyed a major clinical response while 11 enjoyed a partial clinical response of their lupus symptoms.

As more clinical studies are done on Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells, we will learn what other diseases can be treated with this once-discarded substance. Early indications show a very promising future.

St. Petersburg, Florida

St. Petersburg, Florida